Anna Huntington Stanley

American Impressionist

Anna Huntington Stanley

American Impressionist

ANNA STANLEY: AN AMERICAN AT HOME EVERYWHERE

Historically, conquering armies have plundered three areas for spoils of war: land, women, and art. Paradoxically, it was these three things that became driving forces in the life of the American painter Anna Huntington Stanley (1864-1907).

Stanley was born in Yellow Springs, Ohio, shortly before the Civil War ended. She was the fourth child of David S. Stanley, a Major General in the U.S. Army later awarded the Medal of Honor for his valor. Her mother, Anna Maria Wright Stanley, was the daughter of an Assistant Surgeon General of the Army. Raised to endure the demands of military life, she would surely have known the Soldier’s Creed, which pledges to treat others with dignity and respect, and which emphasizes loyalty, duty, honor, and courage. By the time she turned 14, Stanley had already lived in South Dakota, Michigan, New York, Texas, and Washington, D.C.

In 1878, the family moved to Buffalo, where Stanley attended the prestigious Buffalo Female Academy, which provided a studio and a large collection of photographs of European artworks to study. Under the tutelage of Ammi M. Farnham (1846-1922), who had trained at Munich’s art academy alongside the American master Frank Duveneck, Stanley learned to paint in oils and watercolors.

Fig.1

Though her era defined women’s roles primarily as domestic, Stanley’s family actually encouraged her pursuit of an artistic career. In 1882, she enrolled at Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where she studied for three years under Thomas Eakins, Thomas Anshutz, and others. Eakins’s curriculum focused on human anatomy and direct study from live models, both of which were relatively rare in the U.S. and which strongly influenced Stanley’s later work, including her numerous portraits.

At this time, it was difficult for women to gain admittance to European art schools; Paris’s renowned École des Beaux-Arts, for example, did not begin training them until 1897. In 1887, however, Stanley was accepted at the unusually progressive Académie Julian in Paris, where Gustave Boulanger, Gustave Courtois, and Jules-Joseph Lefebvre helped her refine her drawing skills. With an artist-friend, she rented an apartment near the Musée du Louvre and Tuileries gardens.

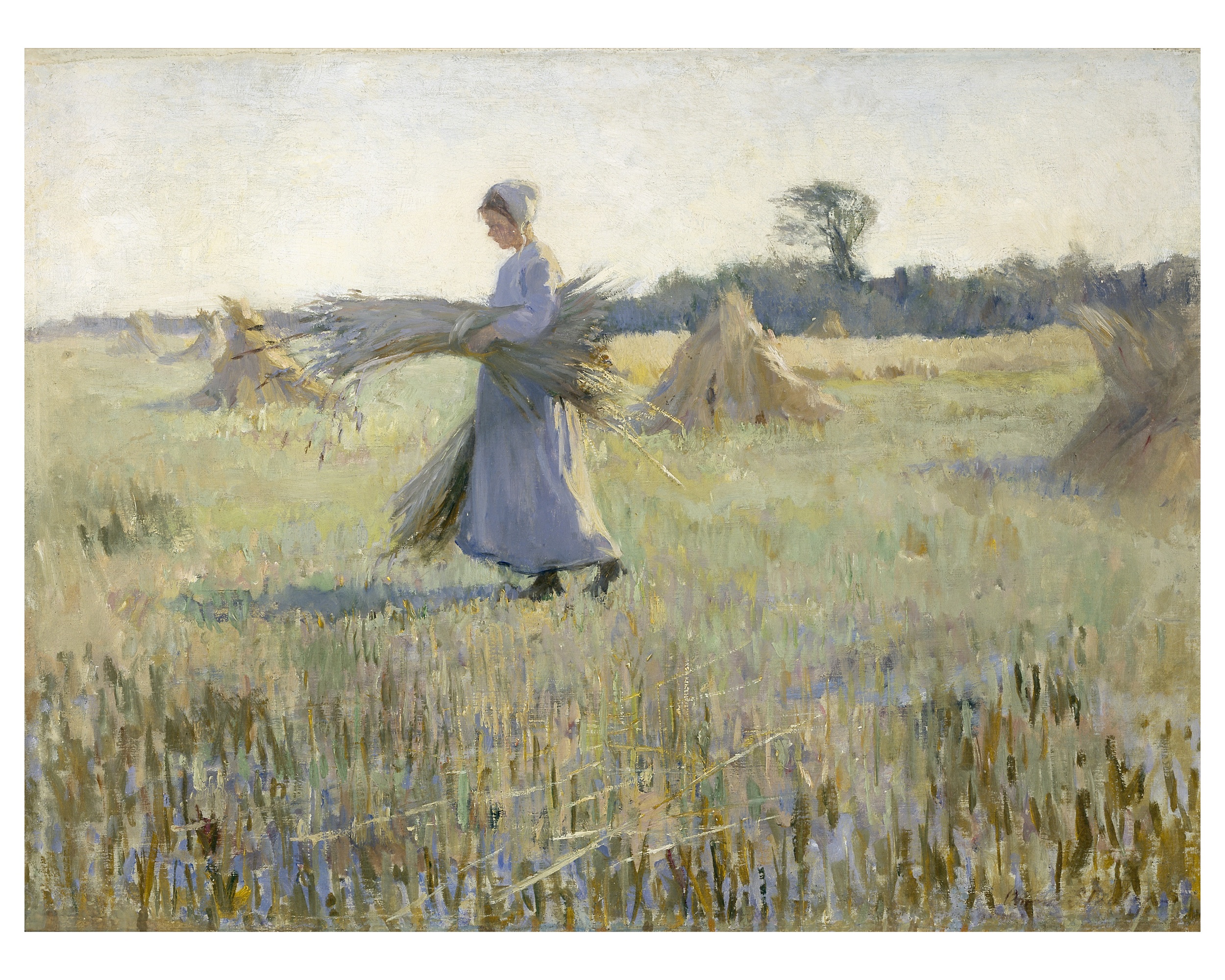

In the summer of 1888, John H. Vanderpoel, a Dutch-American art instructor, arranged for a group of artists to paint en plein air in the Dutch village of Rijsoord, an experience that permanently changed Stanley’s perspective by allowing her to focus on the working class, a choice that reflected her innate understanding of working-class soldiers. Stanley instinctively grasped the substantial contributions that laboring women and children make to society, and so began creating compassionate images of them at work and rest.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

After returning to Paris, Stanley transferred to the Académie Colarossi, where she studied under Courtois and Jean-André Rixens. Here the classes were less structured and offered unclothed male models; for the first time, she rented a studio to share with a friend. In 1889, Stanley returned to Rijsoord, where she further developed her own style in figure and landscape painting. Like those of Eakins, her figures convey a certain potency, a determination to endure regardless of hardships—much like loyal soldiers.

Every artist in Paris longed to have works selected for the annual Salon of contemporary art, where an international reputation could be forged overnight with the right picture. Participation was expensive not only due to entry fees, but also because the artist had to hire models, purchase materials, and transport the resulting works to be juried. In 1888, Stanley’s charcoal drawing, Portrait de Mme. E.H…, was accepted, and the following year two more of her works graced the Salon.

RETURNING HOME

In 1889, at age 25, Stanley returned to the U.S., where her art enjoyed an enthusiastic reception, beginning with two paintings hanging in New York at the National Academy of Design’s annual salon of 1890. That same year, she painted her father in uniform, one of only a few male portraits she is known to have made.

In 1891, Stanley exhibited three paintings at what is now the Detroit Institute of Arts; in 1892, another picture was admitted to the National Academy, and the following year she showed at Veerhoff Galleries in Washington. In 1894, she showed a picture at the Boston Art Club and National Academy, returning to the latter in 1894, 1895, and 1896.

In 1895, Stanley returned to Rijsoord one last time in order to paint for five months, creating works that reflect her growing attraction to impressionism, with more vibrant colors and natural lighting, looser brushwork, and decorative patterning. In 1896, several of these were shown in a solo exhibition at Veerhoff Galleries.

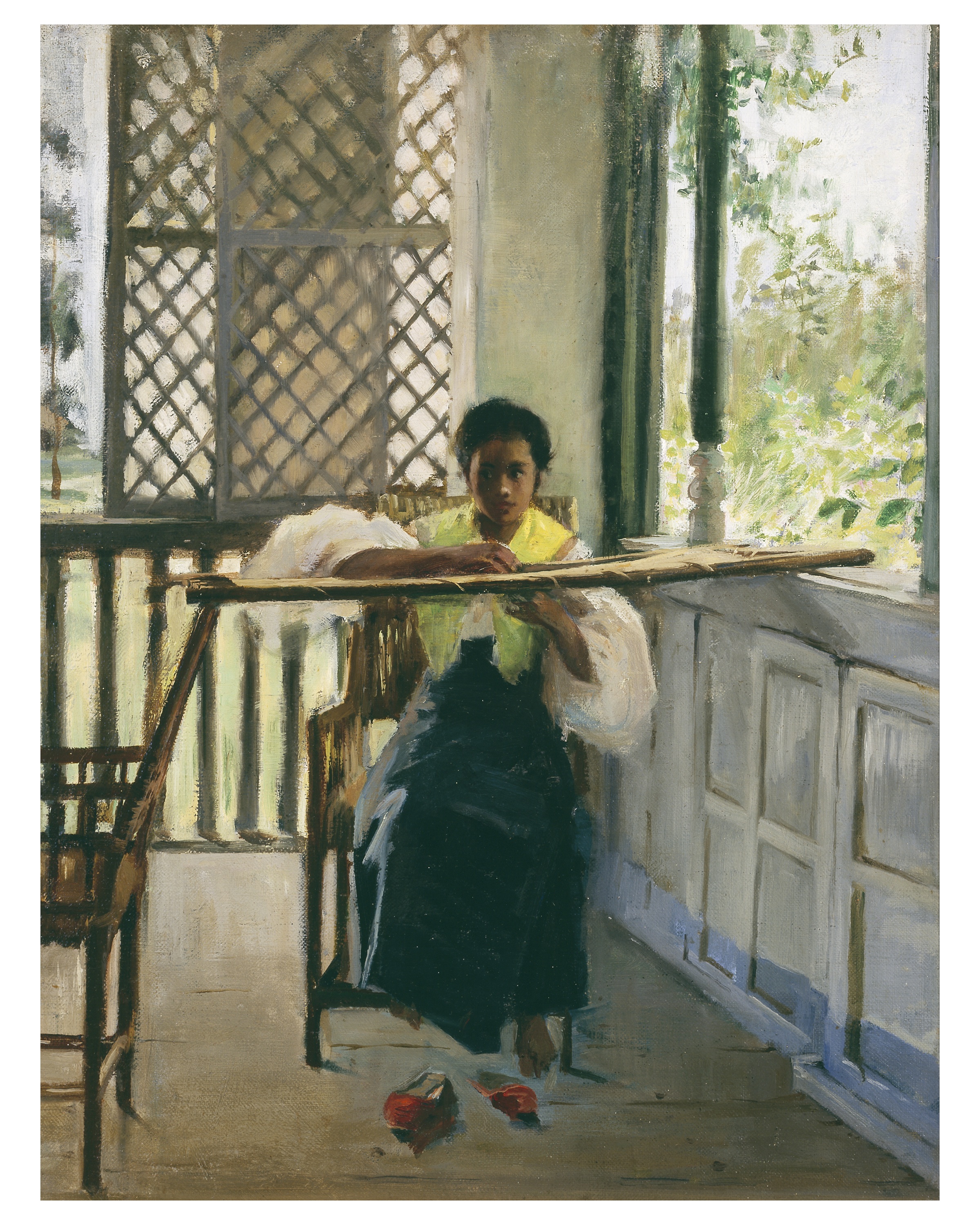

Fig. 4

In order to avoid the distractions of domestic duties, many 19th-century women artists remained single, but in 1896 Stanley chose to marry Lieutenant Willard Ames Holbrook (1860-1932), her father’s former aide-de-camp, and later a Major General himself. They had two sons, and proceeded to live in Arizona, Oregon, Washington, California, Pennsylvania, and even on the Filipino island of Panay (1901). Not surprisingly, Stanley’s time available for painting grew limited, so the appearance of her Spinning Wheel at the Society of Washington Artists in 1897 was one of her last. While in the Philippines, the Holbrooks visited Korea and Japan, and in Asia she painted more than usual, in both oils and watercolors. In 1902, the Holbrooks began a three-year stay in Arizona. Five years later, they moved on to Chester, Pennsylvania, but the artist died there within two years, aged only 42.

Fig. 5

The iconic vistas of nature captured by members of the Hudson River School perfectly epitomize America’s sense of “Manifest Destiny,” yet they generally dwarf the human presence. Anna Stanley took a different approach, conveying her deep compassion for humanity, and for women in particular. As her father once stated in an 1885 address to the cadets at West Point, "labor in all things… fulfill thy ministry."

Since her death more than a century ago, Stanley has been relatively overlooked. To mark the 1976 Bicentennial, however, the U.S. Embassy in The Hague exhibited a large group of her artworks and illustrated letters. More recently (2009-10), Savannah’s Telfair Museums included Stanley in the impressive exhibition, Dutch Utopia: American Painters in Holland, 1880-1914, which also visited the Cincinnati Art Museum, Grand Rapids Art Museum, and Holland’s Singer Laren Museum. That project made the significant point that, in this period, the Dutch countryside offered American artists not only charming subject matter, but also reassured their elite viewers in the U.S.—many of whom were descended from Dutch settlers themselves—that the quaint, rural ways of their ancestors had survived intact. In fact, Dutch cities were growing and industrializing almost as chaotically as American ones, but this reality was typically ignored or minimized by the visiting artists.

Fig. 6

In her lyrical scenes, Stanley recorded the lives of people who might otherwise be forgotten entirely, usually in a muted palette set off with bursts of sunlight that enhance the depth of field and provide the dramatic shadows that flesh out the reality she perceived. Though pleasing today, her scenes of “regular” people sidestep dewy-eyed romanticism to reveal that life was not always easy for them, that life had to be survived, and that its more quotidian aspects should be noted and honored.

Authored by Jane C.H. Jacob, MA: an art historian and president of Jacob Fine Art, inc. (JFAi) in Chicago, a consulting firm specializing in provenance research and issues of attribution. JFAi has been working with the family of artist Anna Stanley to verify provenance and coordinate scholarly publications and exhibition.

Article reproduced courtesy of Fine Art Connoisseur Magazine, originally published in November/December 2014

IMAGE IDENTIFICATION KEY:

Figure 1: Windmill (Rijsoord, Netherlands), ca. 1885 - 89

Oil on canvas 14 x 10 in.

Signed lower right; “Anna Stanley”

Private Collection, Escondido, California

Figure 2: Girl Carrying Sheaves (Harvest – Holland), ca. 1895

Oil on canvas 18 x 24 in.

Signed lower right; “Anna Stanley”

Private Collection, South Hamilton, Massachusetts

Figure 3: Portrait of General Stanley (David Sloan Stanley), c. 1890

Oil on canvas, 26 x 24 ⅛ in.

Signed: Upper left Anna Stanley 1891

The Army and Navy Club, Washington, DC

Figure 4: Filipina Embroidering, c. 1901 – 02

Oil on canvas, 18 x 14 in.

Private Collection, Austin, Texas

Figure 5: Dutch Milkmaid, ca. 1888 – 89

Oil on canvas, 21 x 17 in.

Signed lower left; “Anna Stanley Holland”

Private Collection, Bethesda, Maryland

Figure 6: Sailboats at Sunset, Ilolio, c. 1901 – 03

Watercolor, 6 x 9 in.

Unsigned

Private Collection, Austin, Texas